Monday and Tuesday in Thayer Preparations

We started the week with two lab days to prepare for the rest of the week. The interns spent part of the lab time learning to use drone mapping software. The software allows the drone to fly itself and create mapped areas from the pictures it records. We are hoping this will be applicable in BTW’s future work, from research sites in New England to the Caribbean. Then we spent time preparing all the equipment for a big seagrass coring day Wednesday.

Wednesday’s Big Coring Day

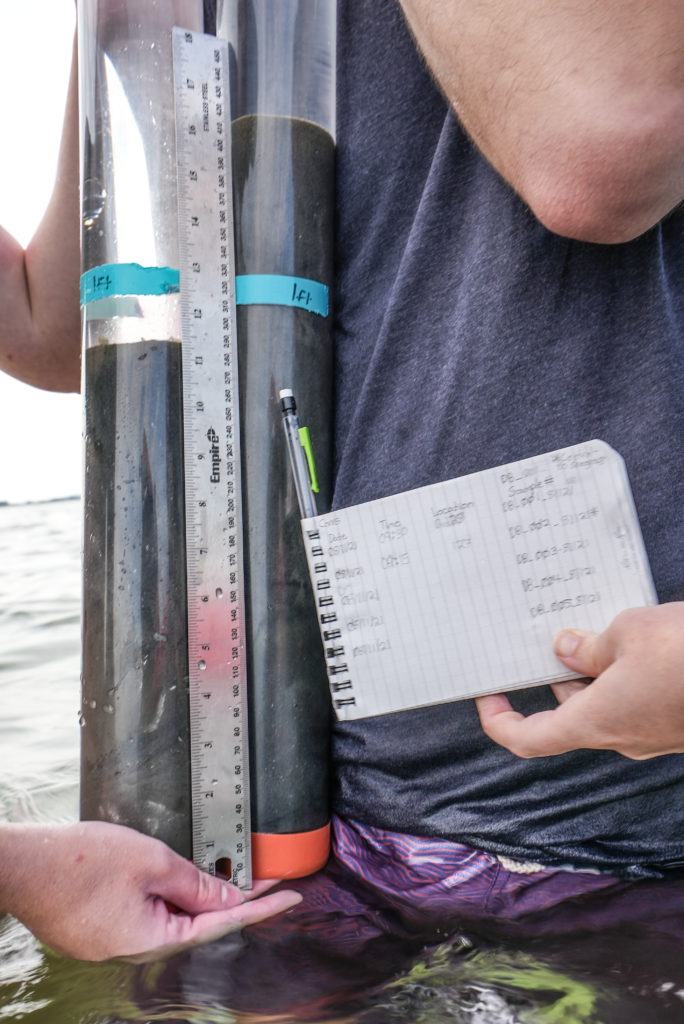

Our team started the day at Duxbury Beach, where we drove out to our EPA-assigned spot, set up corers, and headed out on foot at low tide in search of eelgrass. The last time researchers mapped these beds was eight years ago, and it is clear that a lot has changed since then. We fanned out searching for eelgrass over the next couple of hours, but unfortunately didn’t find any on that side of the channel. We ended up taking a core where we knew the seagrass used to be, and a control core closer to shore. However, oyster farmers pointed us towards seagrass across the bay at Clark’s Island. So Wells, Beneath the Waves’ Blue Carbon Program Manager, headed over in a kayak and successfully took two seagrass cores.

We then packed up and headed back to the Duxbury Beach parking lot to meet Dr. Julie Simpson from MIT. We spent a lot of time troubleshooting our extruding process. We went from trying to push down the tubes through the extruder, essentially those ice cream push pops but for soil and much larger, to hammering the top of the tube down. In excellent field science fashion, we went from Plan A to Plan J. Eventually, we got the samples we needed and handed them over to Dr. Julie to take back to her lab to dry, process, and test carbon sequestration levels.

Credit: Beneath The Waves.

Thursday Regroup and Reorganize

On Thursday, we spent the first half of the day cleaning and reorganizing the coring equipment and setting up all of the tagging equipment for Friday. The second half of the day we spent discussing how we want to analyze all the BRUV footage. As lovely as pretty deep-sea videos are, we need to do something with them. So far, we have gone through trying to identify species, behavior, and numbers. Grace also worked on more TikToks that everyone should check out!

Friday’s Shark Tagging

We arrived at the dock at 6 AM. While all of us interns are not morning people, we are ambitiously driven. We get the boat packed up and push off, heading out to our first stop to drop off the BRUVs. Today we had 2 deep-sea BRUVs to drop, which was a much bigger challenge than expected, as you’ll learn later. Next, we head to where we plan on tagging sharks near Stellwagen Bank. Usually, it takes a long time to catch our first because the chum slick hasn’t spread out yet, but this Friday was different. We relatively quickly caught a blue shark and tagged it. It was a very efficient workup and release. Almost right away, we saw two more sharks. It was a swelteringly hot day, and biting flies were out to kill, but it was overall a very successful tagging day.

Now the retrieval of the deep-sea BRUVs… We returned to where we dropped them and tried to send the release code for them to float to the surface, which we do using acoustic signals. The release code was unsuccessful for the first BRUV we dropped, so we went to where the second one had fallen, and still no luck. After an hour of troubleshooting, we realized that the very hot day had likely exacerbated the thermocline, and created a saline and temperature “wall.” The acoustic signal was therefore bouncing off of this “wall” when we were right on top of it, coming back to the surface rather than communicating with our deep-sea rig below it. When we were farther away, the signal’s path to the BRUV was more gradual and, therefore, not affected by the thermocline. The next challenge of course is spotting these rigs at the surface, which is even more difficult from further away… But luckily, we were able to retrieve both rigs—and all of the data—and finally head back to the dock. We didn’t get back to shore till after dark and dropped everything off back at the lab.

Credit: Beneath The Waves.

Monday Tagging from Harwich Port

Over the weekend, the interns living near Thayer went in to process samples from Friday and restock all the equipment to start tagging again on Monday. On Monday, we started with an early morning out of Harwich Port to tag sharks. After about an hour and a half of boating, we arrived at an area known as The Regal Sword, east of Chatham and Nantucket. As we headed out, we spent time catching bait to use for our endeavors later. The boat ride consisted of casual visits from minke and humpback whales, breaching from afar and passing near the boat. We could even see them engage in bubble-net feeding, a strategy that humpbacks use when surface feeding. A group of them blow bubbles around a school of fish to concentrate them in one area, and feed by lunging with their mouths open through the fish they have trapped.

Not too long after, as we were fishing for more bait, one of our interns, Liza, felt a strong pull on her Sabiki rod. Suddenly, the force seemed to have gained an extra forty pounds. As we were trying to pull in what felt like a very powerful dogfish, the line snapped, and a giant mako shark breached into the air. Awestruck by what occurred, we marveled at what was one of the few makos we have seen this summer. Feeling encouraged by our sudden shark sighting, we were ready to find more. Still, our luck started to wane as it took a bit longer to find the next shark.

At about 1 o’clock, we were able to see three different pods of dolphins jumping near the boat. We deployed our drone and flew it to check out the action, and we were able to get some fantastic shots of them as they were passing by. The rest of the day consisted of seeing multiple blue sharks swim near the boat as we tried to get them close enough to tag. Though we only were able to get a few, the day as a whole was a great mix of whales, dolphins, sharks, and plenty of Greater Shearwaters curiously flocking around our bait.

Credit: Beneath The Waves.

Return to Coring

During this week, we have experienced moments of extreme heat and heavy rainfall. Despite the abnormal weather, we continued our plan on Wednesday as another day for collecting seagrass core samples from Duxbury Bay.

We arrived at Duxbury Beach around 1:00 pm, set up our station and coring gear, and prepared the extruder, i.e., “dirt push pop” for our return. With all our equipment assembled, at around 2:30 pm, we ventured out at low tide to collect three seagrass sediment cores in the previously designated site by the EPA in Duxbury Bay. We reached the seagrass beds about thirty minutes in, and the water level was already about chest height. We were ready to proceed to take our seagrass sediment cores.

Interns pushed the coring tubes into the seagrass meadow until it reached the blue taped line on the tube of about 30 cm. We noticed underwater (with our masks and swim goggles) that the sediment had at least gotten to the designated mark. We were ready to close the end of the tube with an orange cap to prevent any loss of deposit until we returned to our station. So for our first attempt of the day, we ended up collecting two times the necessary amount of sediment than expected; we were ecstatic, for as they always say, “the more, the merrier!”. We collected slightly less deposit from the two seagrass sediment cores (each about 100ft apart). However, we still were able to capture more than 30 cm worth of the seagrass. With the heavy cement-like coring tubes in our arms, we then trudged back to our station.

Upon arrival, we immediately began extracting using the extruder to release the sediment from the tubes into individual bags with different required increments of sediment: 2cm, 3cm, 5cm, 10cm, and another 10cm. We started with the first two tubes. Both had a more slippery and muddy consistency allowing the tubes to slide easier down the extruder. Because of this, we were able to use our preferred method of the ten individual 1 cm spacers attached to the end of the extruder. We individually removed a certain amount of spacer according to each required increment of sediment to mimic (in centimeters) the needed amount of samples to be collected. With the third tube, due to the sandier and thicker consistency of the sediment, we experienced some difficulty pushing the tube down the extruder. Therefore, we had to take an extra step by using a hammer to provide enough force for the tube to slide down more smoothly. And because of the use of a hammer, instead of the spacers, we had to use a marker on the outside of the tube to indicate the increments of sediment needed to scoop out into individual sample bags.

We gathered the samples and put the bags into a bucket for the lab. Interns then planed the samples into the below-freezing freezer of -80°C, where they will be stored until they’re ready to be run and analyzed by the BTW team.

Edited by Nathan Perisic.